Sweeney’s "Edwards the Exegete" and “the Real Jonathan Edwards”

represents a crowning achievement of a dozen years of studying Jonathan Edwards. Doug Sweeney, who was my doctoral advisor at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and who runs a helpful blog on Edwards, has done Edwards scholars and followers a tremendous service in this volume, pulling back the curtain on a foundational aspect of Edwards’ life and thought that has generally been ignored. As Sweeney puts it succinctly, “We fail to comprehend Edwards’ life, thought, and ministry when viewing them apart from his biblical exegesis” (ix).

This monograph offers readers the first synthesis of Edwards’ exegesis across his entire corpus. Other volumes have explored aspects of Edwards’ corpus—particularly Stephen Stein’s fine introductions to Edwards’ biblical manuscripts printed in Yale University Press’s Works of Jonathan Edwards—or examined Edwards’ approach to particular parts of the canon. But Sweeney offers a truly groundbreaking study in analyzing the whole, based on a remarkable mastery of the primary and secondary literature on Edwards and his world, visible in the length and detail of the book’s notes.

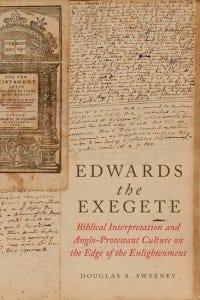

As indicated by the volume title, Edwards the Exegete: Biblical Interpretation and Anglo-Protestant Culture on the Edge of the Enlightenment (Oxford University Press, 2015; source: publisher), Sweeney aims to present Edwards in his broader exegetical and cultural context without outright commending or denigrating Edwards as a biblical exegete. He admits, “I am not an Edwardsean,” and he instead seeks to approach the topic “as a historian, . . . transport[ing] thoughtful readers into Edwards’ biblical world, helping them understand and sympathize with Edwards’ exegesis, from the inside out, before resuming critical distance and evaluating his work from a late-modern perspective” (ix). He accomplishes this goal well.

What exactly can we say about Edwards in his context and how he relates to ours? Sweeney guides readers by splitting his study into five parts. In the first part, he addresses some preliminaries, both providing an illuminating taxonomy of Edwards’ biblical writings and exegetical interlocutors and displaying Edwards’ high view of Scripture. In the remaining parts, he highlights four particular practices that Edwards used most in his exegesis. Each part consists of two chapters, one devoted to an overview of the method and one illustrating the method through a comprehensive study of Edwards’ exegesis on a particular biblical passage or theme, watching him “wade into the finer points of Scripture, working out his biblical vision of reality” (75).

The first of these methods is Edwards’ canonical exegesis, by which he mined the whole of the canon to illuminate its parts. Here one finds an explanation of Edwards’ (infamous) use of typology. Sweeney recognizes that many feel uneasy about Edwards’ approach to types but takes readers into how Edwards viewed them, showing that he “never went beyond what the rule of faith allowed” and “always read types in light of later biblical teaching” (72). To illustrate Edwards’ canonical exegesis, Sweeney explores his treatment of Melchizedek, the priest who appears in Genesis 14, Psalm 110, and Hebrews 5–7. In sum, Edwards “preached the canon whole, trying to help [people] see the beauty of the Bible’s spiritual harmonies, pointing them to Christ from every part of sacred Scripture” (92).

The second method Sweeney highlights is Edwards’ Christological exegesis, something he recognizes many late-modern exegetes find to be excessive. Here again Sweeney withholds assessment, instead aiming to help readers understand Edwards’ exegesis. He explains that from Genesis to Revelation, “Christ shone for Edwards as the star of holy Scripture,” and while he devoted much time to the history, culture, and languages of the Bible, “that natural sense was oriented in reference to the person and work of Christ far more firmly than has been the case for scholars since his day” (111). Sweeney uses Edwards’ reading of the Song of Songs to illustrate his Christological exegesis. While his various notes by themselves, Sweeney observes, “will seem a stretch,” when read together “they form a plausible biblical pattern” that, to Edwards, pointed to “important spiritual truths,” particularly about Christ and his love for the world (125).

Sweeney recognizes as Edwards’ third major method his redemptive-historical exegesis (something I highlight in my book on Edwards’ interpretation of the Psalms). The Bible as a “map of world history” oriented Edwards to God’s purpose in human history with a particular emphasis on Christ’s work of redemption (138). This thrust in Edwards’ biblical interpretation shows his exegesis to be both “unflinchingly eschatological” (a term Sweeney qualifies as anachronistic) and “especially providential”—two phrases that highlight Edwards’ emphasis on God’s purpose and involvement in history (141, 156). Sweeney uses Edwards’ interpretation of the book of Revelation to illustrate how he read the Bible always with an eye to preaching the gospel and highlighting the trajectory of God’s plan of redemption.

Finally, Sweeney describes Edwards’ pedagogical exegesis, the way he discussed and proclaimed Scripture as a guide to faith and life. Sweeney reminds us that this approach captures the day-to-day Edwards, the “clergyman and teacher paid to unpack the text in a pedagogical way” (188). This was the most important exegetical method for Edwards, who underscored that Scripture is “a matter of life and death, to be practiced here and now” (189). To illustrate Edwards’ pedagogical exegesis, Sweeney points to his treatment of justification by faith—a contested issue in Edwards studies, as some argue that Edwards preached an essentially Roman Catholic view of justification. Sweeney shows that, even though Edwards sometimes sounded like a Catholic, “he was not a crypto-Catholic” (204). Rather, “Edwards taught what he did for largely exegetical reasons,” seeking to explain how the apostles Paul, John, and James all agreed and expounding their varied writings “in a canonically balanced way” (217).

One of the ways this volume stands out is that Sweeney gives us both Edwards in his own words and incisive historical analysis of Edwards in his broader exegetical world. In doing so, some readers may finds aspects of Edwards’ exegesis a bit shocking, especially on the Song of Songs and Revelation. This is part of Sweeney’s effort to give a fulsome view of Edwards in his context and to show how he differed from our exegetical instincts today. It reveals how Edwards’ approach to the Bible made sense to him, made sense in the eighteenth century, and sometimes puzzles the modern Bible reader. Regardless of what one does with Edwards’ exegesis, Sweeney’s treatment helps readers understand not only Edwards but also our current exegetical climate.

Along those lines, Sweeney calls Edwards a “‘both-and’ exegete: traditional and avant-garde, edifying and critical, profoundly theological and thoroughly historical.” This helps us see Edwards on the “edge” of the Enlightenment. He was at a hinge of sorts, holding on to an older way of exegesis while engaging the new learning of his day. But as Sweeney notes, the empirical, evidential impulses of late modernity eventually led fewer and fewer to practice his style of exegesis as they opted for “technical” exegesis and “the right of private judgment” (222). For some, this leaves Edwards standing as a bygone of another era. But for others—particularly “those who dare to hope that God is speaking in the Scriptures”—Sweeney argues that Edwards offers “a learned and creative model of biblical exposition that is critical and edifying, historical and spiritual” (223). He leaves it to the reader to decide.

Edwards the Exegete is essential reading for Edwards scholars, and it should also receive a wide readership among Edwards fans, historians of biblical interpretation, and even biblical scholars. The volume helps people understand what Sweeney calls “the real Jonathan Edwards, the heart of whose theology was biblical exegesis. Though a literary artist, metaphysical theologian, moral prophet, college teacher, nature lover, and civic leader, he was primarily a minister of the Word” (218).

*Full Disclosure: I received a complimentary copy of this book from the publisher in exchange for my honest review.