Americans and the Color of Christ

Today, if we ask the question, what color was Jesus?, we will most likely hear that he was dark or brown, like the color of a Middle Easterner. But in America, even if people recognize this likelihood, most envision a white Jesus in their mind’s eye. We, of course, have no known images of Jesus. So how did this view come about?

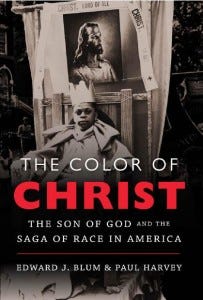

In The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America (University of North Carolina Press, 2012), Edward Blum and Paul Harvey trace the differing visual portrayals of Jesus from the colonial era to our day. I recently listened to the audiobook version of this volume and found that they recount a fascinating—though, at times, disturbing—tale that brings out the diverse ways people have reimagined Jesus and used him for their own purposes in American history, often in ways with tragic racial consequences.

We can highlight some major contours of development here. Interestingly, in the Puritan colonial era, people tended not to picture Jesus as having a particular face at all because they took the second commandment (not to make graven images) so seriously. Instead, when they talked of Christ or what he looked like in their dreams or visions, they described him as not white but light—literally, he shone as a bright light.

In the decades following the Revolution, as the tension over slavery heightened, new images of Christ were created. Many of these images followed the description issued in the Publius Lentulus letter that purported to give a description of Jesus by one of his contemporaries. Everyone knew that this letter was a fraud; it dated to sometime between the tenth and fourteenth centuries (20). But many wanted to believe it was true, and over time, this letter became more influential in developing the white Christ.

At the same time, in antebellum America, blacks identified Christ not with a white man but with the suffering slave. Even Northern whites like Harriet Beecher Stowe connected in their minds the Christ who died on the cross with the black slave being whipped on a tree. The racial tension stemming from centuries of whites enslaving blacks set the stage for a racial battle waged over the color of Christ that would long outlast the War between the States.

In the post-Civil War decades, white supremacists increasingly embraced the Publius Lentulus letter as reliable and promoted a white Christ—the Ku Klux Klan offering the most tangible evidence of this ideology. At the same time, others pushed back to argue that Christ was actually black. This thinking paved the way for the Civil Rights era, a time when many African Americans viewed Jesus as white, influenced by the plethora of white Christ images available. But some clashed by promoting a black Christ, especially through the vehicle of liberation theology in the 1907s, à la James Cone.

By far the most influential depiction of Jesus ever created was Warner Sallman’s Head of Christ (1941). For millions, when they think of Christ, they picture either Sallman’s Jesus or else a Jesus very similar to his painting.

In our own day, with globalization and the rise of the Internet, images of Jesus abound. Few Americans say that Christ was really white since we’ve seen pictures of Middle Easterners on TV and online. And yet Americans tend to picture him that way anyway, simply because of the prevalence of images of white Christs like Sallman’s.

On the one hand, this account highlights how people of all colors have used images of Jesus to assert their power—whether white, black, red, or yellow. In American history, you can find portraits of a Native American Jesus, a Yogi Jesus, a feminine Jesus, a black Jesus, and all kinds of “variations on a theme.” From a historical standpoint, this shows in part that the image of Jesus is so valuable in America that everyone wants either to claim him for themselves or to invalidate him by making a mockery of him. That people use pictures of Jesus for their own purposes should caution us in how we create or view images of Christ.

On the other hand, this account reminds us of the tendency of humans in their fallenness to make God in their own image. This is, of course, the reverse of what happened in the biblical account of creation, when God created man—male and female—in his own image (Gen. 1:26–27). When humans create God in their own image, they domesticate him, distorting his true nature to reflect their own desires.

This use was most clearly visible in the way whites used—and continue, in more subtle ways, to use—images of Christ to perpetuate white power. Many do it with ill motives, while others do it unwittingly. And that should cause us to stop and reflect on how we use images of Christ in our churches and Sunday schools. It certainly gives me pause about the children’s Bibles in our possession and how they might reinforce—albeit unintentionally—erroneous impressions about Christ in the eyes of our children. In what way is the second commandment binding on Christians? What limits do we have in making images of Jesus? And how does the incarnation—God become man—affect or change answers to this question?

In emphasizing diversity and racial tension, Blum and Harvey help us understand the history of how images of Christ have been used in America. At the same time, I think their account misses some of the shared Christian identity that has united many people across races, who focus not on the color of Christ but on their common corruption as fallen humans and their common salvation that comes only through the grace of Jesus.

This recognition of a shared identity does not ignore the ongoing divisions in American Christianity. As the recent riots in Baltimore show, racial tension continues to plague the U.S. As a Christian, I believe Christ offers a true solution to these problems through the gospel, placing all races on the same level: in need of God’s mercy and transformed to be agents of grace to all.

But Blum and Harvey’s The Color of Christ forces us as Christians also to recognize that people don’t always use Jesus and his image in the way that he would want them to. We err when make the Son of God in our own image, for God ultimately wants not for us to make a white Christ, a black Christ, a red Christ, or any other color Christ. Rather, he seeks the opposite, to conform us—of all races, ethnicities, colors—to the image of Christ (Rom. 8:29). In becoming like Christ, we can incarnate “grace and truth” (John 1:17) in each color of the human race, together bringing his light to all.