Frederick Douglass and the Hypocrisy of Antebellum Slaveholding Christians

“Of all slaveholders with whom I have ever met, religious slaveholders are the worst. I have ever found them the meanest and basest, the most cruel and cowardly, of all others.”[1]

These words felt like a terrible blow as I was listening to the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass*, an autobiographical account of Douglass’s life in slavery and eventual escape from it.

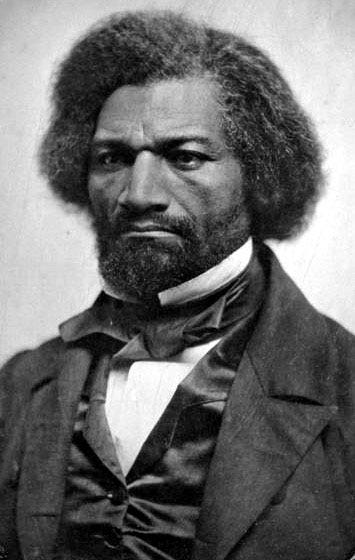

Douglass is a remarkable figure in nineteenth-century America. He amazed the people of his day with his striking intellect and powerful oratory skills. His narrative was meant to validate his genuine slave background and further the abolitionist cause—a cause he championed with great force and effectiveness in the antebellum years.

Arriving at a place of influence was no small feat for Douglass. He rose from a humble position, never knowing his father—whether he was his master or not. He knew his mother only by night, because the slaveholder kept her away from him during the day. Before long, she died, and the boy grew up an orphan.

Having providentially ended up under the ownership of a kindly mistress (at least until her husband intervened), Douglass received the taste of education that led him on a tireless pursuit of completing his studies in learning to read. He credited his master with the wisdom of saying that teaching a slave to read was like giving him a peak at a world beyond slavery, a world of freedom he would never give up seeking. And so it was for young Frederick. He eventually did learn to read, and it kept the itch alive to find his way to liberty.

Douglass’s story is fascinating, and the short book is well worth the read. Yet I was powerfully struck by the religious element in his account, particularly his statement that “religious slaveholders are the worst” of all. How could this be? Why was it so bad being under religious masters?

We could speculate on several possible explanations. For masters, perhaps the knowledge of God’s law led them to be more severe. Rather than reflecting on the gospel truths that nurture the virtues of mercy and compassion, they were easily drawn to passages that they might (mis)use to justify the economic benefit they received from owning slaves, passages that they could rip out of biblical context to keep their slaves in submission.

Also, perhaps masters knew intuitively that there was something not right about owning slaves. And maybe that internal tension was just so grating on them that they took it out on their slaves all the more. Supporting this idea is Douglass’s own observation that slavery was bad not only for slaves but also for slaveholders, wearing on and degrading them.

For slaves, the abuse they received may have stung all the more because they sensed that Christian masters should be different from what they were. As one example, at one point Douglass expected a severe beating from his master, but his master treated him kindly that day. The young slave realized that he withheld the whip only because it was Sunday. When Monday came around, he knew the whip would be loosed to do its bloody work.

Ultimately, it is the hypocrisy of Christians holding slaves and justifying slaveholding that nearly led Douglass away from Christianity altogether. Instead, he had the insight to differentiate between what was true Christianity—the Christianity that followed Christ—and what was nothing but hypocritical Christianity. Douglass’s unsettling remark about religious slaveholders being the worst finds its fullness in the appendix to his Narrative*, where he makes one of the most poignant statements about religion and slavery in antebellum America:

What I have said respecting and against religion, I mean strictly to apply to the slaveholding religion of this land, and with no possible reference to Christianity proper; for, between the Christianity of this land, and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference—so wide, that to receive the one as good, pure, and holy, is of necessity to reject the other as bad, corrupt, and wicked. To be the friend of the one, is of necessity to be the enemy of the other. I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land. Indeed, I can see no reason, but the most deceitful one, for calling the religion of this land Christianity. I look upon it as the climax of all misnomers, the boldest of all frauds, and the grossest of all libels. Never was there a clearer case of “stealing the livery of the court of heaven to sever the devil in.” I am filled with unutterable loathing when I contemplate the religious pomp and show, together with the horrible inconsistencies, which every where surround me. We have men-stealers for ministers, women-whippers for missionaries, and cradle-plunderers for church members. The man who wields the blood-clotted cowskin during the week fills the pulpit on Sunday, and claims to be a minister of the meek and lowly Jesus. The man who robs me of my earnings at the end of each week meets me as a class-leader on Sunday morning, to show me the way of life, and the path of salvation. He who sells my sister, for purposes of prostitution, stands forth as the pious advocate of purity. He who proclaims it a religious duty to read the Bible denies me the right of learning to read the name of the God who made me. He who is the religious advocate or marriage robs whole millions of its sacred influence, and leaves them to the ravages of wholesale pollution. . . .

Such is, very briefly, my view of the religion of this land; and to avoid any misunderstanding, growing out of the use of general terms, I mean, by the religion of this land, that which is revealed in the words, deeds, and actions, of those bodies, north and south, calling themselves Christian churches, and yet in union with slaveholders. It is against religion, as presented by these bodies, that I have felt it my duty to testify.[2]

This is a picture of the hypocritical religion of American slaveholders who professed Christianity—and of any who supported slaveholding in some way. The rhetoric is powerful and inescapable. No doubt there was nuance with some people who owned slaves and acted with some degree of kindness toward their slaves, but they were too often the exception, and even their guilt for participating in the “peculiar institution” at all cannot be so easily absolved.

In contrast, Douglass depicts in beautiful terms that authentic Christianity is that which follows Christ. It is “the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ.” That is well worth pursuing in our own day.

Frederick Douglass in his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass* makes a strong case against Christian hypocrisy—a matter that still merits reflection and action today.

[1] Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, ed. Philip Smith (Mineola, NY: Dover, 1995), 46 (in chap. 10).

[2] Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, 71–74 (in the appendix).

*Amazon affiliate link